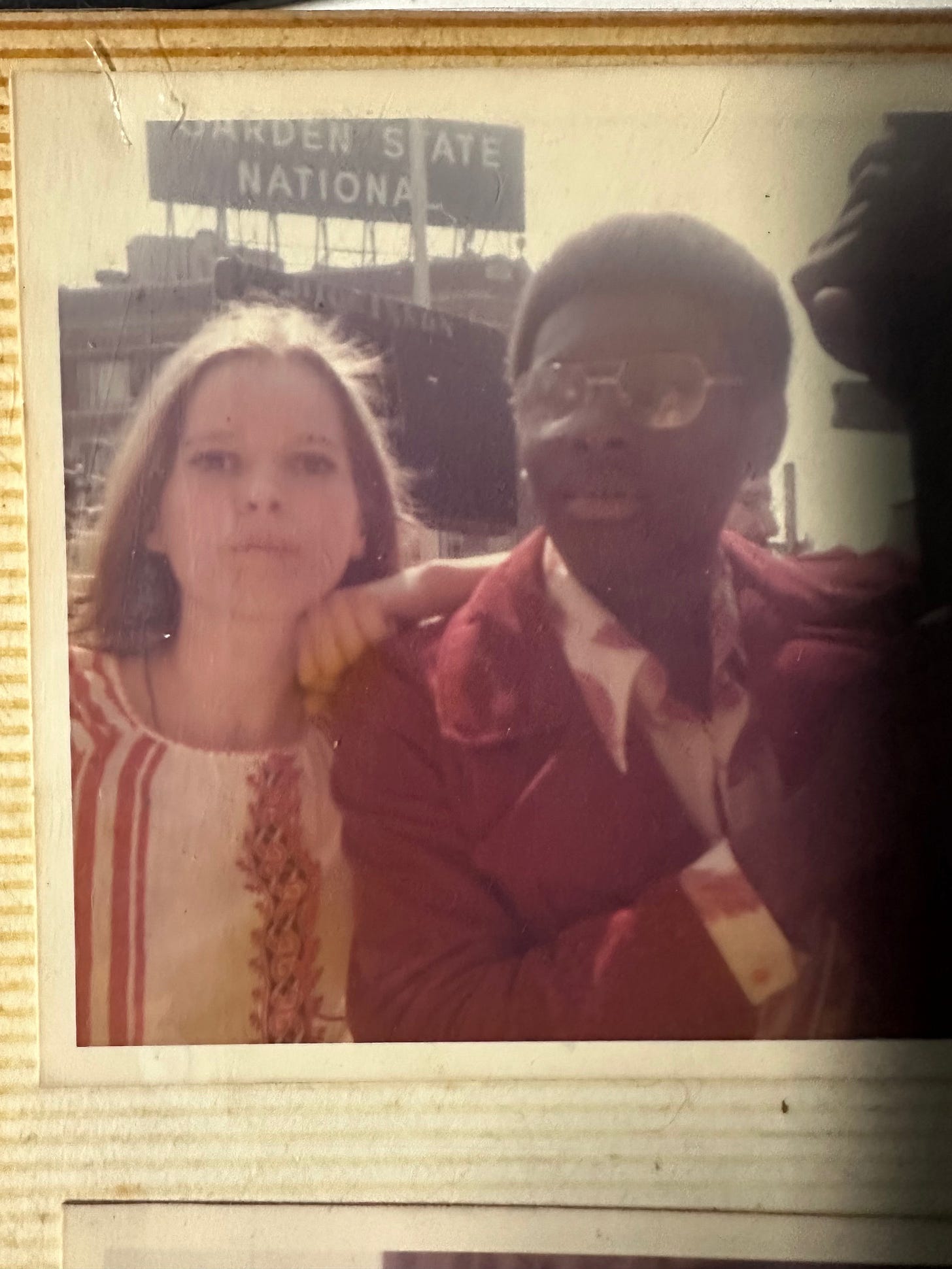

Yesterday, my uncle texted a photo of my mother—his big sister—to my father, my sister, and me. In it, my mom couldn’t be more than sixteen years old. She’s standing with a friend, presumably a classmate, in what my dad and I surmised is Journal Square in the Jersey City Heights, a few short blocks from where she grew up. It’s probably some time in the late ‘60s, maybe the first year or two of the 1970s.

Looking at it, I’m hit with a rare feeling. Probably because, unlike so many other photos of my mother, I’ve never seen this one before. It’s a feeling I’ve never felt when looking at old pictures of my mom.

I don’t know the young woman in this photo.

I mean, I know who this young woman would become. I know the person she was destined to be. But who is this person that I’m looking at? How similar was she to my mother? How different? What changed about this person in the thirteen or fourteen years between this photo and my birth? What changed about her in the two decades between my birth and the time when I considered my mom and me closer to equals than we were parent-child?

I know for certain that the woman I knew was much stronger than the young woman in this photo. Maybe not tougher, because if there’s one thing I know about this young woman, it’s that she was tough as nails, owing to the fact that she had to fight her way out of Jersey City in order to stay alive. At least, that’s how she always described her youth to me. Maybe she was being dramatic. After all, she was a lifelong storyteller. But, what I do know about her childhood and the violence that was one of its constants, I can’t imagine that what she told me was far from the truth.

But the woman she became, the woman that raised me, was stronger than this young woman could ever imagine. Because this young woman didn’t yet understand that strength doesn’t only come in fists.

I know this young woman’s poetry and her essays because I’ve read it in her books and journals. I know her fears and her horrors because of the things she would tell me, when I was old enough, of course. I know her ambitions because she realized some of them. And she was never shy about telling me about the ones she didn’t.

I only know this young woman through stories. Stories she told. So, do I know this young woman at all? And when I think of it like that and I look at this picture, I feel a jealousy of the young man in the picture with her. He knew this version of my mother in a way I never could.

For some reason, I have a similar photo of myself hanging on a small cork board in my office.

In it, I’m driving my old Jeep Wrangler. My hair is long and sunbleached, no doubt from the whole of a late-high-school or early-college summer spent at the beach where I was raised. Judging by the look in my face, I’m either making a joke or singing along to Pavement or Dinosaur Jr or Eric’s Trip or any of the other million bands who were exploding my horizons back then. And a chin. It’s a chin I haven’t seen in more than twenty years.

I don’t remember who took the photo. Probably a lovely young girl who I should have been much kinder to. I don’t quite remember who the person in that photo was. I do know that he walked a fine line between unshakable self confidence and stultifying self doubt. I know that line well because it’s a line I still tiptoe today.

I also know that he dreamed of doing everything I’ve ever done; of working at his favorite record label and touring around the country playing the guitar and seeing his byline in the New York Times and GQ and National Geographic.

If I was able tell him all of this, I don’t know that I would. I wouldn’t want that kid to get lazy, knowing that those successes were headed his way. In fact, those successes were almost purely the result of unrelenting effort, something that kid knew almost nothing about. It was something he had to learn. The kid in that photo cared little about anything beyond new music, light beer, and making out with pretty girls at the beach. He was already lazy. He didn’t need more motivation to be unmotivated.

If I was able to have the same conversation with my teenaged mother, on the other hand, I absolutely would. I’d tell her about her future self. I would tell her that very soon after this photo was taken, she’d meet a man that, for the first time, made her feel safe. I’d tell her that he would take her on a great adventure and that their love would last until the moment she died, just as strong as it was the day they met. I’d tell her that her pain would never go away but that she would learn how to control it. I’d tell her that she would become a marvelous mother because I know that would be one of her first questions.

I don’t think I’d tell her she wouldn’t become a professional writer. Or, if I did, I would tell her that she wouldn’t for an instant regret the choices that led her to where she was heading. I don’t think I’d tell her that I make my living writing stories because I don’t know if jealousy was part of this young woman’s makeup, even if it wasn’t part of my mother’s.

I’d have far more questions for the young woman I see in the photo than I would answers. But this is all imaginary and they’re questions I’ll never get answers to (mostly. Uncle did just clear up that the photo of my mother was taken during her senior year of high school, 1971 or ‘72, with her friend Isaac, with whom she was starring in a production of Jesus Christ Superstar), so I’m not sure the point in asking them here.

This is one of those newsletter editions where you might be wondering, “What the fuck does this have to do with being a father, Mikey?”

Because I view fatherhood through two lenses simultaneously. One is forward facing, one is rear facing. And through these photos, I’m doing exactly that: looking back, while also looking forward. In my teenage mother and my teenage self, I see future versions of my own babies. I see them as teenagers on the precipice of life and wonder if they’ll be more like my mother or me. We were both full of self doubt but hers was protected by toughness whereas mine was tempered by confidence. I hope I can raise them to be both tough and confident but without the self doubt those things were (are) shielding for my mother and me.

In these photos, I also see a version of my children that exists only for a moment. Just like they did when they were tiny, just as they are now. In these photos, my mother and I exist only for an instant in time. And in a few years, my own kids will sit exactly there, teetering precariously on the edge of the rest of their life, having no idea what kind of wonder, what kind of change, and what kind of growth is in store for them.

I can’t tell them what’s going to happen because I don’t know. But even if I could, I’m not sure I would.

It’s beautiful look back and forward. I am confident that your mom is with you on this journey.

This is a great piece, man. Really enjoyed it. Parenting being simultaneously looking backwards and forwards is bang on the money!